15 Absolute Worst Jobs in History No One Wanted to Do

Work has changed so dramatically over the centuries that some past occupations feel almost unreal today. These roles demanded hard effort and often endangered those doing them. Toxic fumes, punishing hours, and grim tasks shaped daily life. No wonder they’re considered the absolute worst way people could be employed.

Reading through these, it’s striking to see how survival itself once counted as part of the job description.

Gong Farmer

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

In Tudor England, men known as gong farmers spent nights wading through cesspits filled with human waste. Using shovels and buckets, they cleared excrement to prevent overflowing pits from threatening public health. Underground air was often filled with choking gases that knocked workers unconscious.

Chimney Sweep

Credit: Canva

In 18th and 19th-century Britain, children as young as six were sent up narrow chimneys to scrape away soot. Many flues were scorching hot because fires still burned in the hearths below. Scalded limbs and crushed ribs were common injuries, and long exposure to soot often led to disfiguring cancers.

Matchstick Girl

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Factories using white phosphorus filled the air with fumes that rotted jawbones from within. Young women spent endless hours dipping and boxing matches, coughing through shifts that seemed endless. Their 1888 strike in London forced change, though countless workers had already suffered irreversible damage before reforms appeared.

Burlak

On the Volga River, long human chains hauled barges upstream by strapping ropes across shoulders. Muscles tore under strain as men trudged through mud all day. Some collapsed mid‑pull and were left behind while crews pressed forward. When winter froze rivers, these same workers scrambled for odd jobs to survive.

Snake Milker

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Snake milkers risked lethal bites each day. Catching venomous snakes in the wild was hazardous, as one misstep could lead to a fatal strike. They pinned a snake’s head and pressed fangs against containers to extract venom. Few survived long enough to master the craft.

Army Drummer

Credit: iStockphoto

Young drummers on Civil War battlefields signaled troops through rhythmic commands. Without radios, these beats relayed orders to advance or retreat. They were often targeted deliberately. Many also carried wounded soldiers, fetched supplies, and dug graves, all while unarmed and exposed to constant danger.

Groom of the Stool

Credit: Youtube

This court position meant assisting a monarch during private moments and recording details of health. Though trusted enough to hear sensitive discussions, the day‑to‑day work was far from dignified. Exposure to disease and the sheer awkwardness of duties kept the role from being envied, even with its unusual proximity to power.

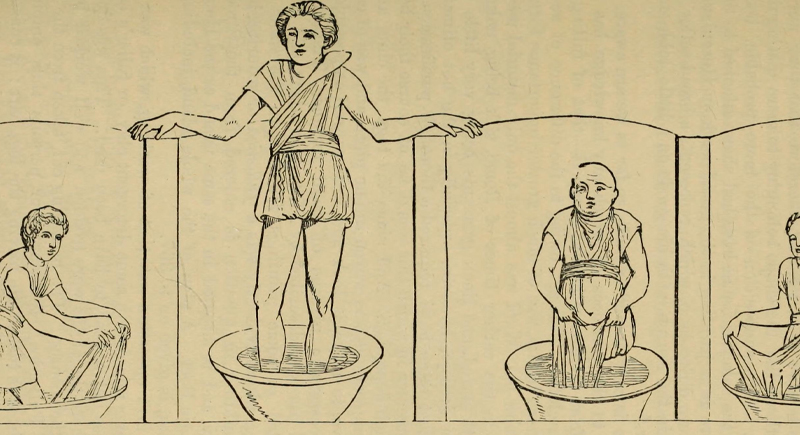

Wool Fuller

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Before chemical detergents, wool was softened by stomping it in tubs of urine. The acrid fumes stung lungs while long shifts left legs numb. Workers often suffered skin infections from constant exposure. Despite harsh conditions, the cloth industry relied on its labor, and few outside the trade ever considered how fabric was prepared.

Arming Squire

Credit: iStockphoto

During battles, arming squires maintained a knight’s heavy armor, often under fire. They rushed to fix dents, replace straps, or clean weapons without any protection themselves. After fights, they scrubbed mud and blood using harsh substances like aged urine. Injury was frequent, but the job offered little recognition.

Pure Finder

Credit: Getty Images

In 19th century cities, dog feces were collected to supply tanneries, as the enzymes softened leather. Pure finders knew which routes produced the best haul and guarded them from rivals. Handling waste daily brought constant risk of infection, and the smell clung to them for hours.

Leech Collector

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Medical practices once required live leeches, so collectors waded through marshes barefoot to lure them. Swarms latched on, leaving dozens of bleeding wounds that often became infected. Days were spent combing ponds, then scraping leeches into jars. Overharvesting nearly wiped them out, but buyers paid well enough that collectors kept returning.

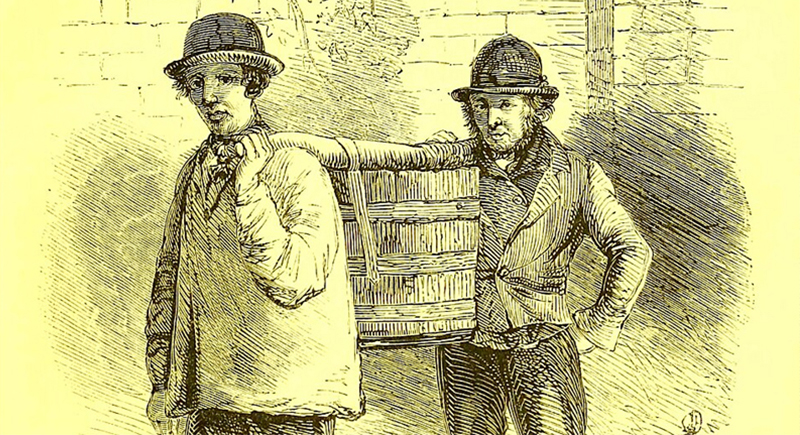

Tosher

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Beneath Victorian streets, these scavengers searched sewers for valuables that had been washed away by accident. Lantern light barely cut through the filth, and sudden floods could sweep a worker away. Toxic air sometimes caused sudden blackouts mid-search.

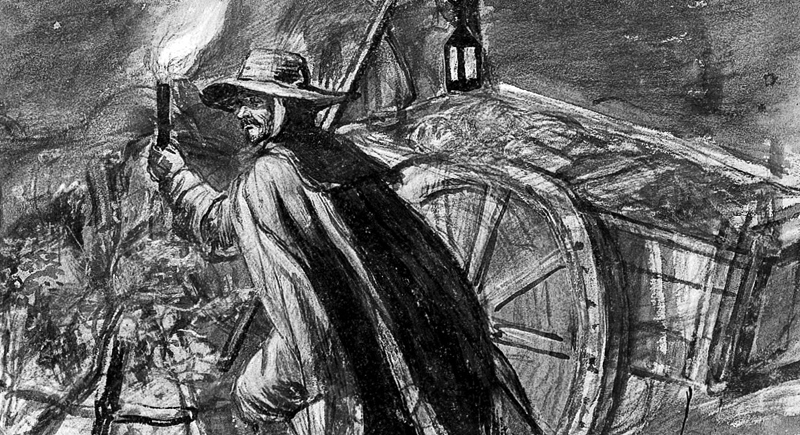

Plague Bearer

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

During outbreaks, these workers collected bodies from homes and alleyways. They loaded carts and dug mass graves, often breathing in air heavy with decay. Many lived near churches, but neighbors avoided them, fearing disease.

Rat Catcher

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Urban areas overrun with rodents created a dangerous market for rat catchers. They captured rats by hand, risking bites that frequently became infected. Some sold live rats for blood sports, while others supplied them to laboratories.

Resurrectionist

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Resurrectionists exhumed fresh graves under the cover of night to supply medical schools with bodies. They hauled corpses through mud and often faced angry mobs or patrols. The smell and risk of infection were intense, yet demand for cadavers drove many to the trade.