14 Boycotts That Commanded the World’s Attention

A boycott is a form of protest, for moral, social, or political reasons, against a person or organization. It is a mass refusal to buy products, services, or even just associate with them. The purpose of carrying out a boycott is to cause economic loss, and by this method persuade the person or organization to alter the practice or policy that people are protesting.

Public shaming and mass avoidance likely have a long history, but the term “boycott” started with a real man by that name.

Boycotts have been used successfully against individuals, companies, cities, states, and even entire countries.

In the Social Media Age, a boycott can be started with just a hashtag. Here’s a list of memorable boycotts from history.

1) The First Official Boycott

Charles Boycott, a land manager in 19th century Ireland, is the man who’s responsible for the term boycott. Wikipedia

The term boycott comes from a man by the name of Boycott.

In 19th century Ireland, wealthy, absentee Englishmen owned most of the land. They would hire a Land Manager to look after their estates and collect rent from tenant farmers. Charles Boycott was the Land Manager for the absent Earl of Erne.

In 1880, after a bad harvest, the Earl’s tenants demanded their rents be lowered by 25 percent. The Earl offered them 10 percent. When the tenants wouldn’t accept this, the Earl ordered Boycott to evict any farmers who did not pay their rents.

Local Irish shunned Boycott and anyone associated with him; no one would take over empty farms on the Earl’s land and local businesses would not sell anything to Boycott, including food. The Captain was forced to leave for Dublin, and even tried to move to the United States, but his reputation followed him and any business that worked with him was threatened with a “boycott.”

In 1888, the Oxford English Dictionary first included the word boycott.

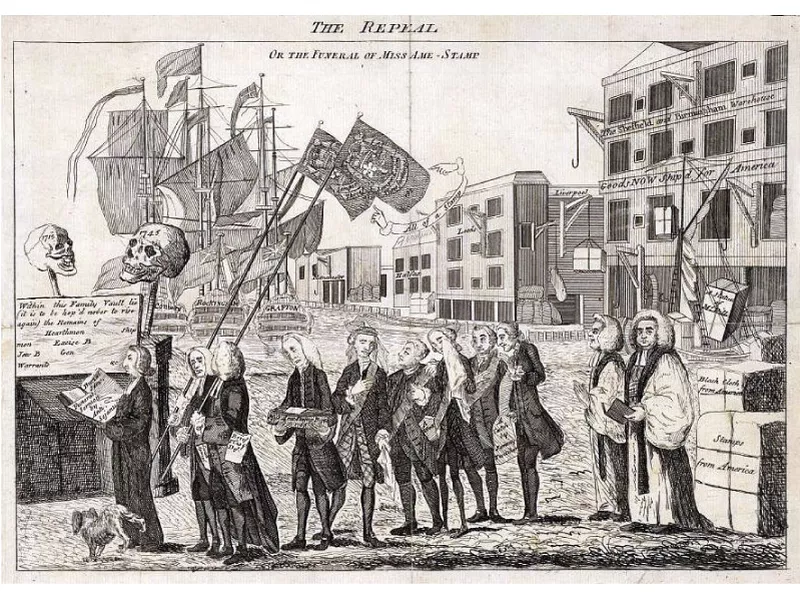

2) The Stamp Act

After the colonists carried out a successful boycott of British goods, Britain repealed the Stamp Act in 1766. Wikimedia Commons

After fighting the French and Indian War of 1763, Britain was deeply in debt and needed to raise money. Deciding that the American colonies would be a good source of revenue, Britain passed a series of taxes on sugar and other goods, concluding with the Stamp Act of 1765. The Stamp Act was a direct internal tax, designed to raise money to pay the cost of keeping English soldiers in the New World.

The colonists protested, calling it “taxation without representation,” given that Americans were not allowed to vote for Members of Parliament and maintained that only colonial assemblies had the right to tax them.

After the colonists carried out a successful boycott of British goods, and physically threatened tax inspectors, forcing most of them to resign, Britain repealed the Stamp Act in 1766.

3) The Slave Sugar Boycott

In 1791, abolitionists failed to persuade the English Parliament to pass a bill calling for an end to slavery in the country’s colonies. The abolitionists then called for a boycott of Caribbean sugar. Sugar from the New World, together with rum, cotton, coffee, and tobacco, relied on slave labor. The boycotters hoped that economic pressure might force the end of the exploitative trade in human lives.

The activist and author William Fox published a pamphlet calling for English households to refuse to purchase “slave sugar.” At the height of the boycott, some 400,000 homes were estimated to have either stopped using sugar or switched to non-Caribbean sugar.

Importers of sugar from the East Indies – where slave labor wasn’t used – took advantage of the boycott to label their products, stating that their sugar was not made by slaves. Households in Regency England proudly displayed these jars to show guests that they supported the sugar boycott.

Sugar sales dropped by a third in the first two months of the boycott, and many grocers either refused to sell Caribbean sugar, or stopped selling sugar entirely. Over the next two years, sales of other sugar rose ten-fold.

Abolitionists brought back the boycott in the 1820s in another attempt to end slavery in the British Empire.

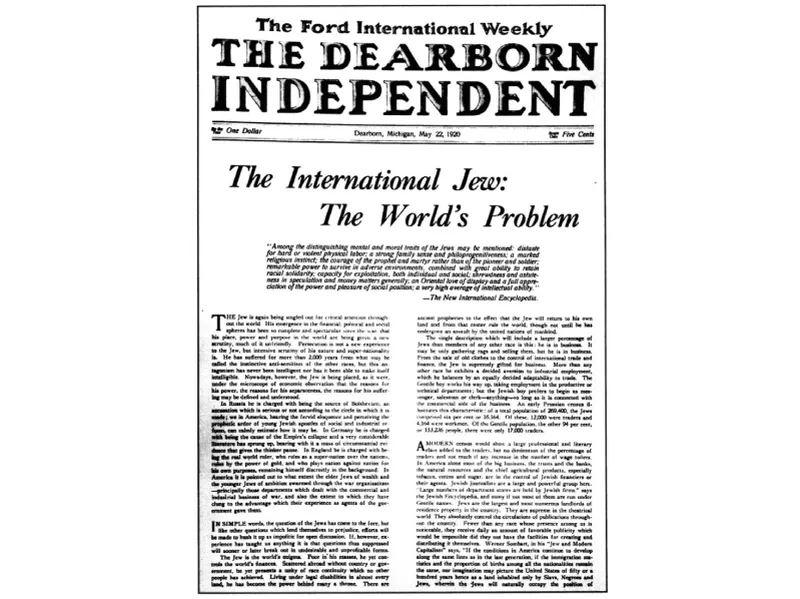

4) The Ford Motor Company Boycott

In 1927, a boycott of Ford vehicles caused Henry Ford to apologize and shut down the Dearborn Independent, a newspaper he owned. Wikimedia Commons

Henry Ford, the founder of the Ford Motor Company, was known to have strong anti-Jewish prejudices. Ford ran a weekly newspaper in the 1920s – the Dearborn Independent – that published anti-semitic articles.

While Ford claimed he never wrote them, the articles were published under his name. The Anti-Defamation League sued Ford for libel and helped to organize a boycott. Both Jews and many liberal Christians joined the boycott and refused to buy Ford cars.

Fox Film Corporation threatened to show footage of wrecked Ford cars in their pre-movie newsreels across the country. Ford finally apologized and shut down the Dearborn Independent in 1927, as a result of his car company’s slump in business.

5) The Salt March

In 1930, Gandhi thought boycotting English salt would be a good way to start his campaign of mass civil disobedience. Wikimedia Commons

In 1882, England passed the Salt Act, which forced its Indian subjects (India was a colony of Britain at the the time) to buy heavily taxed salt from the English. Indians were not allowed to collect or sell salt.

A young Indian named Mohandas Gandhi had returned to his native India after spending 20 years living in South Africa and began working as an activist for Indian independence.

Gandhi decided that defying the Salt Act, or boycotting English salt, would be a good way to start his campaign of “satyagraha,” or mass civil disobedience.

In 1930, Gandhi and thousands of his followers marched to the sea to make salt from seawater. Millions of Indians carried out similar protests across the country and the British authorities arrested more than 60,000 people. Reports in international newspapers of British police violently beating peaceful Indian protestors caused international outrage.

Gandhi would go on to organize similar non-violent boycotts of English manufactured goods, putting more pressure on the British government. Gandhi later called on Indians to spin and weave their own cloth, in a successful boycott of English fabric.

6) The Alabama Bus Boycott

Rosa Parks, whose refusal to move to the back of a bus touched off the Montgomery bus boycott and the beginning of the civil rights movement, is fingerprinted in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1956. AP Photo / Gene Herrick

In 1955, Rosa Parks, who was black, refused to give up her seat at the front of a bus in Montgomery, Alabama, for a white man. Despite African-Americans making up 75 percent of public bus ridership, racial segregation “Jim Crow” laws in the South forced blacks to ride in the back of buses, while front seats were reserved for whites.

Black leaders called for a boycott of all city buses. For over a year, African-Americans car-pooled, walked, took taxis, or rode bikes instead of using buses.

The boycott lasted 381 days (and nearly bankrupted the bus company) until the Supreme Court ruled that segregation on any form of transport was against the law. The city of Montgomery passed an ordinance prohibiting racial segregation on buses, and the Civil Rights Movement in America had its first successful boycott.

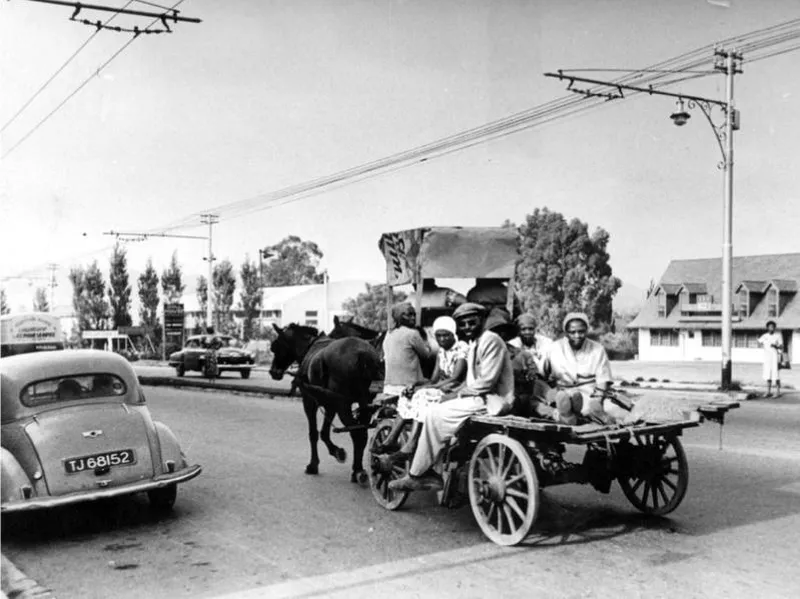

7) South Africa’s Bus Boycott

During South Africa’s bus boycott, people from numerous townships refused to use the bus system, walking up to 20 miles each day instead. artsandculture.google.com

After a sizeable fare increase on buses in 1957 in Johannesburg, South Africa, people from numerous townships in the city refused to use the bus system, walking up to 20 miles each day instead. As many as 60,000 riders were involved in the boycott.

Blacks in South Africa had successfully protested fare hikes before – in 1943 and 1944 – and may have inspired the American bus boycott in Alabama.

The strike lasted six months until the local Chamber of Commerce agreed to subsidize fares, so that they would stay at the old level.

As the Montgomery bus boycott kicked off the Civil Rights Movement, so the Johannesburg boycott began to mobilize blacks to protest their country’s system of Apartheid.

8) The Delano Grape Boycott

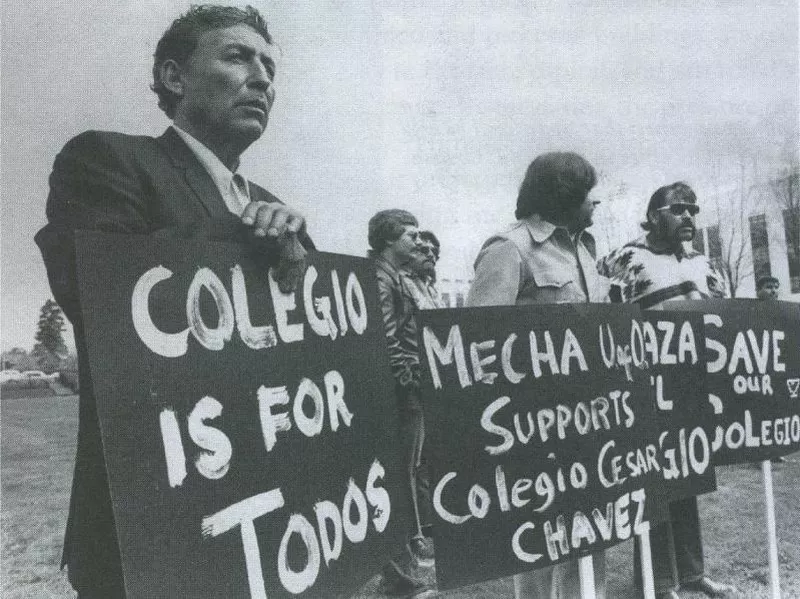

The Cesar Chavez-led Mexican-American National Farmworkers Association helped organize a successful boycott of grapes, which led to improved collective bargaining agreements with farm worker unions. Wikimedia Commons

In 1965, Filipino-American farm workers went on strike against grape growers in the Delano region of California, demanding better pay and working conditions. A week later, the Mexican-American National Farmworkers Association, led by Cesar Chavez, joined them. The two groups merged, forming the United Farmworkers of America.

Chavez quickly became the public face of the movement. He asked dock and warehouse workers to join the boycott and refuse to load or unload grapes. His request was successful. Thousands of tons of grapes were left to rot on docks. Inspired by this success, Chavez decided to take his boycott to the American people and publicly called for a nationwide boycott of Delano grapes.

Chavez had read about Gandhi’s Salt March, as well as the Montgomery bus boycott. He was determined that the grape boycott would remain non-violent and enlist public sympathy.

Millions of people stopped buying grapes. By 1970, the boycott had succeeded. Grape growers signed collective bargaining agreements with farm worker unions for the first time, ensuring that more than 10,000 farm workers received better pay, benefits, and working conditions.

9) The Nestlé Boycott

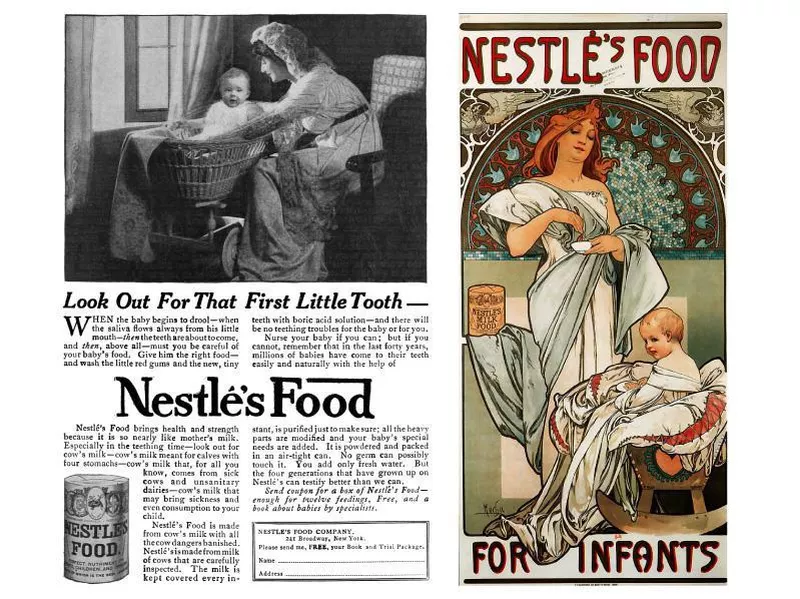

In 1977, the Infant Formula Action Coalition first called for a Nestlé boycott. Wikimedia Commons

Nestlé is a Swiss-based multinational company, which makes a wide range of food items, including infant formula. Groups such as the International Baby Food Action Network and Save the Children accused Nestlé of using aggressive and unethical marketing strategies to persuade mothers in developing countries to use infant formula over breast milk. Nestlé denied these charges and sued critics for libel.

In 1977, the Infant Formula Action Coalition first called for a Nestlé boycott. The boycott spread to Europe and beyond. By 1984, feeling the effects of the long action, Nestlé met with boycott organizers and agreed to abide by an International Code of Marketing for Breast-Milk Substitutes, drafted by the World Health Assembly. The boycott was lifted.

However, in 1984, groups in the UK felt that Nestlé was once again marketing infant formula unethically and resumed the boycott, which continues to this day.

10) South Africa Boycott

As a result of a boycott of the country over its Apartheid policies, many international companies left South Africa, causing large revenue and job losses. Wikimedia Commons

In 1986, the United States Congress enacted the Anti-Apartheid Act, which banned South African imports and airlines from the U.S., and prohibited foreign aid being sent to the country. As a result, many international companies left South Africa, causing large revenue and job losses.

In 1990, then-leader of South Africa, F.W. de Klerk, lifted the government’s ban on the African National Congress – Nelson Mandela’s party – and freed all political prisoners.

Finally, in 1993, after de Klerk announced that South Africa would hold free and open elections for everyone, both white and black, ending the old racist system of Apartheid, the U.S. sanctions were lifted. In South Africa’s first truly-democratic elections, Nelson Mandela became the country’s first black leader.

11) The Taco Bell Boycott

The Coalition of Immokalee Workers’ protested outside of YUM! headquarters, the corporate owners of Taco Bell, in Louisville, Kentucky, in 2004. Brian Bohannon / AP Photo

For many years, farm workers – migrants from Mexico, Haiti, and Guatemala – in Florida’s tomato growing region were forced to endure low wages, abuse, sexual harassment, and “slave-like” working conditions.

In 1991, the Coalition of Immokalee Workers (CIW) formed to protest for better working conditions. Despite the CIW’s well-organized campaigns of work stoppages, farmworker wages remained below the poverty line.

The CIW decided to target companies that bought the tomatoes, instead of the growers. In 2001, the CIW called for a nationwide boycott of Taco Bell, to force the company to accept responsibility for abuses in their supply chain.

The CIW also targeted national retailers, such as Whole Foods and Wal-Mart.

After four years, the boycott against Taco Bell succeeded. The restaurant chain agreed to ensure they would only buy from growers who provided higher wages and better working conditions for farm workers.

12) The NFL Boycott

Colin Kaepernick (center) and two of his then-San Francisco 49ers’ teammates kneel during the national anthem before the team’s NFL football game in 2016 in protest of racial injustice and excessive police force in the U.S. Marcio Jose Sanchez / AP Photo

In 2016, Colin Kaepernick, then a quarterback with the San Francisco 49ers, dropped to one knee while the national anthem was being played. Kaepernick said he did this to protest racial injustice and excessive police force in the U.S. and started a movement known as “taking a knee.” The campaign went viral. Kaepernick wasn’t signed by any NFL teams the following year.

Kaepernick’s supporters urged fans to boycott NFL games, as network ratings are what bring in advertising revenue and partnerships. The petition site, Change.org, called for an NFL boycott and was able to get more than 200,000 supporters.

It’s unclear if the boycott was successful. While Sports Illustrated reported that NFL viewer numbers were down almost 10 percent in 2017, they had also declined by 8 percent the previous year, when there was no boycott. Critics of the NFL also point to a growing concern about football violence as being a factor in the ratings decline.

So far, ratings for the 2018 season are bouncing back.

13) The North Carolina Boycott

North Carolina state House members speak during debate prior to a vote in 2017. North Carolina lawmakers eventually voted to roll back the state’s “bathroom bill” in a bid to end the backlash over transgender rights that has cost the state dearly in business projects, conventions, and basketball tournaments. Brian Blanco / AP Photo

In 2016, North Carolina passed a controversial bill – known as the “Bathroom Bill” – that limited legal protection for the LGBT community and set rules about toilet usage in public buildings. Gay rights advocates criticized the bill and called for a boycott of the state until it was repealed.

Almost 30 counties, seven states, the District of Columbia, and 29 cities barred employees from traveling to North Carolina on business.

Numerous professional and collegiate sports bodies, including the National Collegiate Athletic Association, the Atlantic Coast Conference, and the National Basketball Association, cancelled events in North Carolina or moved them to other states. Entertainment, film, and broadcasting companies canceled planned filming and stated they would not schedule any new projects in the state until the bill was repealed.

In the end, North Carolina lost more than $3.76 billion in revenue, according to an Associated Press report. The controversial bill was finally repealed in 2017.

14) The NRA Boycott

David Hogg (center), a student at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, holds the hand of fellow student Caspen Becher as he and other demonstrators lie on the floor at a Publix Supermarket in Coral Springs, Florida in 2018. AP Photo / Wilfredo Lee

After a mass shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, in which 17 people were killed, anti-gun activists began to call for a boycott of the National Rifle Association (NRA), the gun rights lobbying organization, to pressure lawmakers into passing stricter national gun control laws.

Some of the activists leading the call for a boycott were survivors of the shooting, including David Hogg, then a 17-year old senior.

Hogg and fellow survivors turned to social media to publicize their case. Hogg suggested that people should also boycott the state of Florida, which is heavily dependent on tourism, and where state representatives refused to pass gun control legislation. If lawmakers won’t listen to students, Hogg wrote in a tweet, “maybe [they’ll] listen to the billion dollar tourism industry in FL.”

The boycott succeeded in persuading 17 organizations to drop either their endorsement or financial support of the NRA, including airlines, car rental companies, banks, and others. Retailers have also placed new restrictions on gun sales.